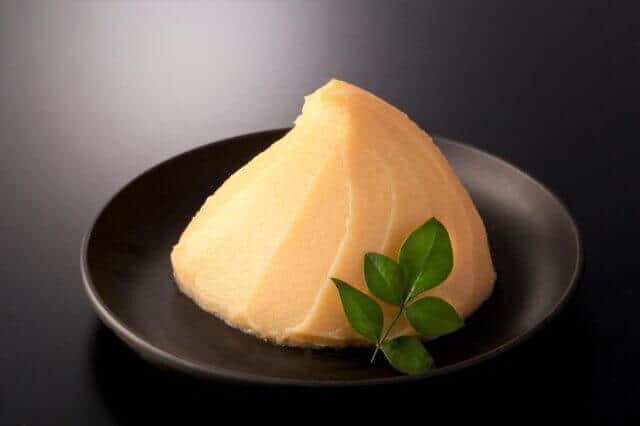

Discover the essence of Shiro Miso, a beloved variety of Japanese miso known for its creamy texture and mild sweetness. This traditional condiment plays an important role in Japanese cuisine, especially in regions like Kyoto and Kansai. Explore more about this versatile ingredient and its culinary applications by reading the full article.

What is Shiro miso?

Shiro miso, also known as white miso, is a type of rice miso that is creamy and sweet. It’s commonly used in Japan’s Kinki region, Okayama, Hiroshima, and Kagawa Prefectures, with Kyoto’s Saikyo miso being a famous variety.

To make white miso, soybeans are peeled and boiled, then mixed with rice malt and salt. Unlike other rice miso, white miso uses a higher ratio of rice malt to soybeans. The aging process, similar to making amazake, involves maintaining a temperature of 50°C or higher, which turns the rice malt into sugar, giving the miso its sweetness.

Shiro Miso Origin

The tradition of Kansai white miso dates back about 200 years. It began when Tambaya Shigesuke, a master brewer from Tamba, was requested by the Imperial Palace (now the Kyoto Imperial Palace) to brew miso for the Imperial Court’s cooking. Kyoto and the Kansai region were home to many tea masters and literary figures, fostering an elegant imperial court culture. In contrast, samurai, who frequently engaged in physical exertion, preferred miso with a stronger saltiness. They also needed a type of miso that could preserve well as military rations.

This cultural environment also contributed to the development of Kyoto cuisine. After the Meiji Restoration, the capital moved from Kyoto to Edo (now Tokyo), and Kyoto became known as Saikyo. This is how Saikyo miso got its name. “Saikyo Miso” is now a brand name belonging to a miso manufacturing company descended from Tamba-ya Mosuke.

Difference between Shiro miso and Aka miso

Shiro miso (white miso) and aka miso (red miso) differ in both color and production methods. Aka miso refers to miso that turns red or brown after aging and can be made from rice, barley, or soybeans. Shiro miso generally refers to a sweeter type of rice miso.

Shiro miso is aged for a short period, while aka miso is typically made by steaming soybeans, mixing them with other ingredients, and aging them at room temperature for six months to a year. During this extended aging, amino acids from soybeans and sugars from rice or barley undergo a Maillard reaction, darkening the miso and enhancing its flavor.

Aka miso is also saltier than shiro miso because it needs a higher salt content to stay fresh during its long aging process. Thus, the longer aging period not only gives aka miso its darker color but also a richer taste compared to the milder, sweeter shiro miso.

Shiro Miso FAQ

- What can you substitute for white miso?

If you don’t have white miso, you can substitute it with another type of miso by adding sugar and mirin to mimic its sweetness. However, while this combination can approximate the flavor of white miso, it may not fully capture the unique aroma and sweetness imparted by rice koji.

- How to determine shiro miso?

To determine if a miso is white miso (sweet miso) or another type of white-colored miso, such as Shinshu miso, check the salt content and primary ingredient. Sweet white miso has about 5% salt and is primarily made from rice, while other white miso, like Shinshu miso, have around 10% salt and are primarily made from soybeans.

How to make Shiro Miso?

In producing white miso, soybeans undergo a dehulling process to remove their thin skins using a special machine. This step is crucial for achieving the fine, creamy texture and the desired white color of the miso. The skin can turn reddish-black during aging, which would affect the color. Therefore, removing as much of the skin as possible is essential.

Then, they will make it by boiling and steaming soybeans using “kaboshi taki.” This process involves agitating the boiling pot to remove skins and scum, then replacing the water multiple times until the soybeans turn white. This method differs from the steaming process used for regular miso, where pressure cookers are often employed to steam the soybeans quickly.

The rice koji used in white miso must have strong saccharification and proteolysis abilities and be early ripening. Unlike regular miso, where the optimal temperature for koji-making is 35-38°C to produce protease, white miso requires a higher temperature, up to 45°C, to increase amylase-based decomposing enzymes. This process enhances the sweetness of the miso but with the addition of proteolytic enzymes needed for soybean fermentation.

Locals will mature the white miso at a high temperature of 55°C, suitable for saccharification, and the process is completed in about three days. This rapid aging process, similar to making amazake, involves artificially maintaining the high temperature. In contrast, regular miso, with a higher salt content, takes much longer to mature, often about a year if naturally fermented, or three months at around 35°C in accelerated fermentation.

Where to buy Shiro Miso?

Komatsuya ((有)小松屋)

Komatsuya’s sweet, low-salt white miso is crafted from 100% domestically grown rice (rice koji) and soybeans. This traditional, handmade miso is produced without additives and undergoes natural fermentation. The result is a miso with a clean taste and gentle sweetness, making it popular among children and those who prefer milder flavors.

Kokonoe Miso (白味噌の九重味噌)

Kokonoe Miso specializes in white miso, utilizing rice koji known for its robust saccharifying enzymes. This high-quality rice koji is meticulously handmade by skilled artisans, a process that cannot be replicated by machines. Among numerous renowned white miso producers in Kyoto, Kokonoe Miso diligently endeavors to create exceptional white miso.

Summary

We hope this exploration of Shiro Miso has provided you with insights into its craftsmanship and cultural importance in Japanese cuisine. As you continue to delve into the world of fermentation, perhaps you’ll find parallels in other traditional Japanese foods like natto, each with its unique fermentation methods and flavors. Expand your culinary knowledge and appreciation by exploring more about Shiro Miso and its counterparts.

You can check some Japanese miso dishes that we know you would like to try too.

Comments