Japanese sweets often symbolize the seasons with nature-inspired designs. On New Year’s Day, stores display sweets featuring zodiac signs and good luck symbols. Among them, “Hanabira Mochi” is a treat associated with New Year’s. Despite the name, it doesn’t resemble flowers. So, why “Hanabira Mochi”? Let’s explore its origins in today’s article!

What is Hanabira Mochi?

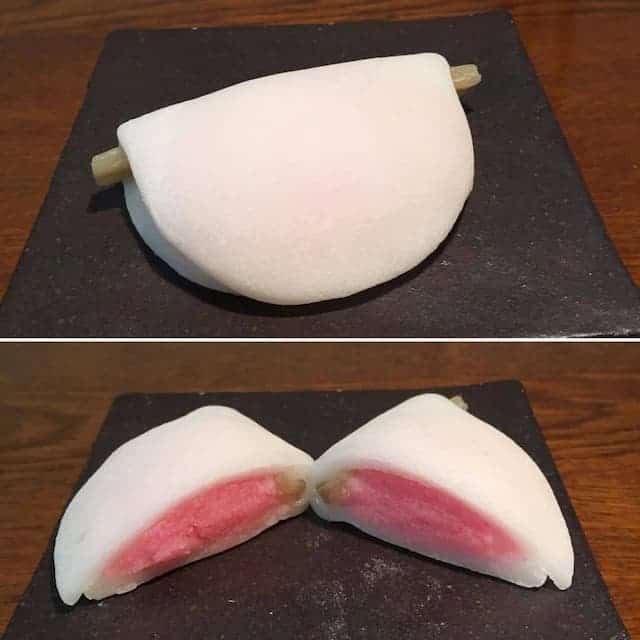

Hanabira mochi is a pretty Japanese sweet shaped like a pale pink petal on a white dish. It’s made by folding a round rice cake to look like a flower petal and hiding burdock inside. Some burdock peeks out, adding charm. This sweet is inspired by plum blossom petals, symbolizing white plum blossoms, often enjoyed during New Year’s celebrations with matcha tea.

The charm of hanabira mochi lies not only in its appearance but also in its representation of Japanese culinary artistry. With each bite, one can savor the harmonious blend of textures and flavors that make this sweet a beloved part of Japanese culture, symbolizing purity and beauty.

It features two types of rice cakes: a thin, flat, and round white rice cake or a red Hishi-mochi at the center of Gyuhi. On top of the Hishimochi, it is folded in half, incorporating white bean paste, a touch of white miso sauce, and shredded burdock root stewed in sweet soy sauce.

But why stack two rice cakes? To trace the origins of hanabira mochi, we journey back to New Year’s Day in the imperial palace. Interestingly, hanabira mochi didn’t start as a sweet. Instead, it’s believed to have begun at Kawabata Doki, a Kyoto sweet shop supplying rice cakes exclusively to palace affiliates.

Flavor and taste of Hanabira Mochi

This mochi isn’t just sweet; it has a hint of saltiness, thanks to the miso bean paste inside the rice cake. Most of the miso used is white miso. The delightful blend of sweetness and saltiness is a significant appeal of these flower petals.

Moving on to the burdock root wrapped in rice cake, it’s known as Fukusa burdock stewed with honey. It’s sweet, but the distinct vegetable flavor of burdock remains intact. Notably, the contrast between the burdock’s firm texture and the rice cake’s softness is also intriguing.

When you take a bite, you experience a delightful mixture of sweetness and saltiness, as well as softness and firmness. Moreover, many crimson varieties use red beans to achieve their pale color, and you’ll also detect a subtle red bean flavor. It’s worth mentioning that while flower petal rice cakes are commonly enjoyed with matcha, they also pair nicely with matcha’s slight bitterness.

History of Hanabira Mochi

Hanabira Mochi in Palace Tradition

In the Imperial Court, on the third day of the New Year, there’s a special tradition centered around “Hishi-hanabira.” This tradition is the root of what we now know hanabira mochi. Hishiagi is a dish made by folding flat white mochi, adding red Hishi mochi on top, and including white miso and burdock simmered in syrup. It’s about 15 cm wide and not very sweet.

Because Hishiagi’s mix of mochi and miso is similar to a dish called zoni, they also call it “Miyachu-zoni” or “Wrapped Zoni.” Hanabira mochi appeared when they made Hishi-buri smaller, added sweetness to the mochi, and changed the miso to miso bean paste.

Throughout history, rice cakes (or mochi) have been used for offerings to gods and in various events. The round white mochi was made to look like lucky plum petals, hence the name “Hanabira Mochi.” Its name, Ryo-mochi, possibly comes from it being similar to Ha-mochi and Hishi-mochi. So, the name “hanabira mochi” also originates from Ryo-mochi.

Why did they start eating Hishi-no-song in the palace? We’re not sure, but it’s thought to go back to the Heian period because “The Tale of Genji” mentions 菱葩.

The Heian Era Longevity Ritual

In the Heian period, the Imperial Court held a ceremony called “tooth hardening” on New Year’s Day to eat tough foods and wish for a long life. They lined up hard ingredients like Kagamimochi, Shishi meat, venison, radish, and salted sweetfish.

The idea behind connecting teeth and longevity was that the number of teeth could reveal someone’s age. So, they believed strong teeth meant a longer, healthier life. Eating hard foods at the beginning of the year was thought to toughen the teeth and promote longevity.

While the exact timing is unclear, they used to eat the hard ingredients on layers of round mochi and hishimochi. Later on, the ceremony was simplified, and they switched to round and diamond-shaped rice cakes, along with Miyauchi zoni containing salted sweetfish and miso.

In the Edo period, burdock root was changed to resemble salted sweetfish in a diamond shape. Today, the Imperial Family still enjoys this on the third day of the New Year, preserving this age-old tradition.

Spread from Urasenke Tea Ceremony

During the Meiji period, when the Emperor’s residence relocated to Tokyo from Kyoto, it marked a capital shift. Michiki Kawabata, a rice cake deliverer to the palace, chose to stay in Kyoto and lost his palace job. Unfazed by this setback, Kawabata ventured into crafting sweets for tea ceremonies, giving rise to Japanese sweets during this era.

Around this time, Gengensai Sosho, a tea master of the Urasen family, introduced Hishiha to the Imperial Palace and suggested its use in the January tea ceremony’s “first pot.” With approval from the Imperial Court, Kyoto-based sweet maker Michiki Kawabata took on its production.

Through experimentation and refinement, Michiki Kawabata tailored Hishiha to suit tea ceremonies, culminating in the creation of a flower petal mochi infused with rice cake sweetness. Beyond the Meiji period, this mochi retained its status as a cherished delight for the first tea gathering of the new year, beloved by tea ceremony enthusiasts.

As it became an integral part of tea ceremonies, this mochi spread across the country, becoming a symbol of New Year’s good luck. Diverse Japanese confectionery stores offered unique variations, introducing elements like miso bean paste or even substituting burdock with carrots. Exploring different shops each year offers a delightful way to savor the array of flower petal mochi flavors.

Additionally, hanabira mochi became a part of Osechi, the traditional New Year’s feast, alongside sweet dishes such as chestnut kinton, sweet boiled burdock, lotus root, and sea bream-shaped rakugan. These dishes express gratitude to the gods for a fruitful harvest and convey wishes for a bright future. Hanabira mochi, steeped in tradition and symbolism, continues to enhance New Year celebrations, serving as a testament to cultural heritage dating back to the Heian period. Enjoy its flavors while reflecting on this enduring tradition.

Hanabira Mochi FAQ

- Why is it called “Hanabira” Mochi?

-

Despite its name, which means “flower petal mochi,” its shape is more like a half-moon than a flower petal. The name might originate from its resemblance to the petals of plum blossoms.

- What is the significance of Hanabira Mochi in traditional Japanese culture?

-

In the Heian period, there was a ceremony called the “ceremony of hardening teeth” in the Imperial Court, where foods resembling Hanabira Mochi were consumed to pray for a healthy and long life. This suggests that Hanabira Mochi has historical roots in auspicious celebrations and longevity wishes.

How to make Hanabira Mochi?

Ingredients

| Ingredients (for 10 pieces) | Amount |

| Candied Burdock | |

| Burdock Root | 2 pieces, 10 cm each |

| Togijiru (rice water) | |

| Granulated Sugar: 100g | 100g |

| Water | 140ml |

| Dough | |

| Jōyako (Fine Wheat Flour) | 70g |

| Shiratamako (Sweet Glutinous Rice Flour) | 50g |

| Water | 180cc |

| Granulated Sugar | 120g |

| Food Coloring | Pink |

| Katakuriko (Potato Starch for Dusting) | |

| White Miso Filling | |

| White Anko (Sweet Bean Paste) | 140g |

| White Miso Paste | 25g |

Method

First, wash the burdock roots with the skin intact.

Next, peel the skin using a knife, leaving them white.

Then cut two pieces into 10 cm lengths. Soak the burdock in Togijiru (rice water) for 1 to 2 hours.

Boil the burdock until they become tender, occasionally piercing with a bamboo skewer (add water as needed to keep them submerged).

Soak the boiled burdock in water for about 30 minutes to remove the togijiru odor.

Cut the burdock into 60% to 80% lengths. Boil them in a mixture of water and honey with boiled granulated sugar for 2 to 3 minutes.

Turn off the heat, cover the pot, and let it sit overnight.

Place the white anko (sweet bean paste) in a heat-resistant bowl and cover it.

Microwave it at 500W for 2 minutes.

Add the white miso, mix until smooth, then cover with plastic wrap and let it cool.

Once cooled, divide it into 10 equal parts.

In a bowl, mix jōyako and shiratamako. Gradually add water and granulated sugar while whisking until smooth.

Microwave the mixture at 500W for 2 minutes and stir. epeat microwaving and stirring until the dough is firm.

Divide into 10 equal parts. Color one portion (70g) pink.

Roll into sticks on potato starch-covered surface. Shape white dough into a 10 cm by 7 cm ellipse.

Place smaller pink dough on top of white dough.

Add honey-pickled burdock in the center. Put white miso bean paste in front of the burdock.

Fold in half to create Hanabira Mochi. That’s how you make Hanabira Mochi! Itadakimasu!

Where to enjoy Hanabira Mochi?

Tsuruya Yoshinobu (鶴屋吉信)

Tsuruya Yoshinobu is a famous traditional Japanese sweet shop in Kyoto. Many people choose Tsuruya Yoshinobu for gifts to clients and important individuals. They have a product called “Gosokyou” (Imperial Palace Mirror), which reflects their elegance. What’s unique is that they don’t call it “Hanabira Mochi.” When you take a bite of their soft gyuhi (rice flour dough), it brings happiness instantly.

Suetomi Takashimaya (末富 髙島屋京都店)

Suetomi serves a delightful specialty: Thick Habutae Mochi with Petals. It outshines competitors with its chewy, flavorful rice cakes. When you bite into one, you’ll experience pure joy and luxury. The addition of burdock lends a fantastic taste to this Japanese sweet. It’s my top pick from Suetomi, offering a unique and satisfying dessert experience that beats other options in town.

Tawaraya Yoshitomi

Tawaraya Yoshitomi is a tiny Kyoto confectionery shop known for its cozy size. They make incredibly smooth rice cakes in an elegant and inviting atmosphere. Unlike other places with thicker petal mochi, Tawaraya Yoshitomi serves a more delicate and petite option, ideal for those who prefer a smaller, graceful treat. It’s the perfect place for anyone who wants to experience Kyoto’s traditional charm on a smaller scale.

Takeaway

In summary, Hanabira Mochi is a delightful Japanese treat that looks and tastes great. Its colorful and petal-like appearance shows Japanese skill. The mochi is soft, chewy, and sweet, making it a tasty treat. People enjoy it during ceremonies or just for fun. Hanabira Mochi represents Japan’s culture and cooking talent. It brings happiness and memories to people who try it. This special treat is a symbol of Japan’s rich food history and makes people happy, whether they’re from Japan or visiting. It’s a sweet tradition that continues to bring joy to many. If you’re interested in making your own, how about following our recipes?

If you’re a fan of mochi, check out the articles below for more fascinating reads!

Comments