Japanese sake has many different tastes, like fruity, light, and sweet. It can be confusing for beginners who want to try it because there are so many types and they don’t know which one to choose or where to buy it. Let’s start by learning about the basics of Japanese sake, especially “Daiginjo”.

Knowing the differences between Daiginjo sake and other types can make enjoying Japanese sake more fun. Also, we’ll give you tips on picking Daiginjo sake, enjoying it, and suggest some good ones for you to try. You can use this information to help you when you’re picking sake.

What is Daiginjo?

Daiginjo sake stands as a revered category within the world of Japanese sake, distinguished by its meticulous craftsmanship and exceptional quality. It holds a prestigious position as a specific name sake, denoting its premium status among sake varieties.

What distinguishes Daiginjo is its rigorous production process, which involves the careful selection of ingredients such as white rice with a rice milling ratio of 50% or less, rice koji, water, and sometimes brewing alcohol. This meticulous selection ensures a refined flavor profile and exquisite aroma, making Daiginjo a favorite among sake enthusiasts seeking an elevated drinking experience. With its smooth texture and complex yet balanced taste, Daiginjo embodies the pinnacle of sake brewing artistry, cherished as a prized treasure in the realm of Japanese beverages.

Japanese sake is broadly classified into “Tokutei meisho-shu” (Special designation Sake) and “futsu-shu” (ordinary sake) based on differences in raw materials and production methods. Furthermore, Tokutei meisho-shu is further classified into eight types based on ingredients, rice polishing ratio, and manufacturing methods.

| Ingredients/Rice Polishing Ratio | Rice & Rice Koji | Rice & Rice Koji + Brewing Alcohol |

| >= 50% | Junmai Daiginjo-shu (純米大吟醸酒) | Daiginjo-shu (大吟醸酒) |

| >= 60% | Junmai Ginjo-shu (純米吟醸酒) | Ginjo-shu (吟醸酒) |

| >= 60% or special manufacturing method | Tokubetsu Junmai-shu (特別純米酒) | Tokubetsu Honjozoshu (特別本醸造酒) |

| >= 70% | – | Honjozoshu (本醸造酒) |

| Not specified | Junmai-shu (純米酒) | – |

If you like Ginjo, click here for details. Or see here to find more about Junmai-shu.

History

The origin of Nihonshu

Japanese sake is made from rice, rice koji, and water. It probably started around the time when people in Japan started growing rice.

Long ago, around 2000 years ago, people think rice growing began in Japan. But some people say rice was being grown even earlier, during the Jomon period. During this time, it’s believed rice fields spread, and people might have been making sake from rice.

Making sake was considered sacred, especially a method called “Kuchikami no sake.” In this method, shrine maidens chewed rice in their mouths. They did this because they believed it was for the gods.

There’s a story about a sake called “Yashiori no sake” in Japanese mythology. It’s said to be the first sake made in Japan. Legend has it that Susanoonomikoto, a god, made it to defeat a dragon. However, some people say this sake wasn’t made from rice, but from nuts or fruits. We’re not sure if people knew how to make sake before they started using rice, and we don’t know where it was first made.

History and Transition of Nihonshu

Let’s take a look at the history of Japanese sake through each era from the Asuka period. We’ll briefly explain how Japanese sake was treated in each era and how it became popular like it is today.

Asuka Period to Nara Period

In the early Nara period, the “Harima Province Fudoki” was compiled, which stated, “Mold grew on rice offered to the gods, so sake was made and offered.” Since rice mold and sake brewing are directly connected in the writing, it is believed that sake brewing using the prototype of rice koji was already widespread.

Also, during the Asuka and Nara periods, there was a ban on alcohol for farmers, so alcoholic beverages including Japanese sake were not common for ordinary people. However, there were exceptions, and it is said that sake brewing and drinking were allowed during special events such as “agricultural rituals” to celebrate a good harvest.

Heian Period to Sengoku Period

From the Asuka period to the Heian period, sake brewing was carried out at the Imperial Court. However, as the country gradually became chaotic, the brewing techniques used at the Imperial Court began to spread to the general public, leading to sake brewing being practiced in places such as sake breweries, temples, and shrines.

Then, during the prosperous Kamakura period (1185), commercialization thrived. Japanese sake started to circulate as a product of equal value to rice. In terms of brewing technology, they used techniques resembling modern sake brewing, such as “firing” and “step brewing,” from the Muromachi period to the Sengoku period.

Edo Period

After the end of the turbulent period, small-scale sake brewing began to take place even in ordinary villages. However, as the sake market gradually expanded, larger breweries emerged, and eventually, the shogunate imposed control over large-scale sake brewing. This was called the “sake share system,” and it was accompanied by the collection of sake taxes and certain restrictions on sake brewing.

However, with the spread of sake brewing, the sale of Japanese sake also increased, becoming more familiar to ordinary people. Sake such as clear sake and doburoku were sold, and it is said that drinking sake was possible inside retail stores. Also, in the mid-Edo period, tools for heating sake and sake cups became popular, and it is said that the number of people enjoying warmed sake increased.

Meiji to Showa Period

In the Meiji period, the abolition of the “sake share system” allowed for new sake brewing licenses, leading to a surge in breweries. However, increased sake taxation due to inflation caused a significant burden on brewers, resulting in a drastic reduction in breweries by the late Meiji period. Despite this, Japanese sake’s popularity continued to grow, becoming a household staple and commonly available in one-sho bottles.

Meanwhile, advancements in science and technology propelled modern Japanese sake brewing forward. Innovations such as thermometers, advanced rice polishing machines, and enamel tanks contributed to this progress.

However, during the Showa era, the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War and World War II led to restrictions on rice, the main ingredient for sake brewing. This caused a temporary decline in sake production. To cope, many synthetic sake products mimicking Japanese sake’s flavor emerged and were consumed during this period.

Postwar to Present

After the war, Japan entered a period of rapid economic growth. Consumption of Japanese sake increased, and mechanization in sake brewing progressed, making it possible to brew sake throughout the year with the introduction of air conditioning facilities.

Furthermore, to differentiate themselves from major breweries, small and medium-sized sake breweries began to focus on production methods such as junmai-shu, ginjo-shu, and honjozo-shu. With the spread of these different brewing methods, the “Sake Brewing Quality Standards” were applied in 1990, and labeling became mandatory on labels. This led to the popularization of terms such as “Tokutei meisho-shu” (Special designation Sake) and “futsu-shu” (ordinary sake).

Additionally, products such as draft sake, cloudy sake, and sparkling sake began to increase during this period, marking a turning point in further diversification of Japanese sake.

What is the best way to enjoy Daiginjo sake?

We recommend two ways to enjoy Daiginjo sake are as follows:

- Drink it chilled.

- Drink it in a wide-mouthed sake vessel.

Let’s explain each in detail.

Drink it cold

Daiginjo has a delicate smell and taste. It’s best to drink it cold, about 10 degrees Celsius. Keep it in the fridge. Take it out 15 minutes before you want to drink it. Then it will be just the right temperature.

When you drink sake cold, you can smell it better. But as it gets warmer, you can taste its sweetness, richness, acidity, and bitterness more. But remember if it gets too cold, it might be hard to smell or taste it well.

Drink from a wide-mouthed sake vessel

The taste can change depending on the vessel (the cup or glass you drink sake from). Sake goes well with various types and shapes of vessels like ceramics, glass, or metal. For enjoying the aroma of Daiginjo, we recommend to use a wide-mouthed wine glass. Also, some Daiginjo sake has a color close to amber, so using a clear vessel allows you to enjoy its appearance as well.

Top 3 Recommended Japanese Sakes Daiginjo

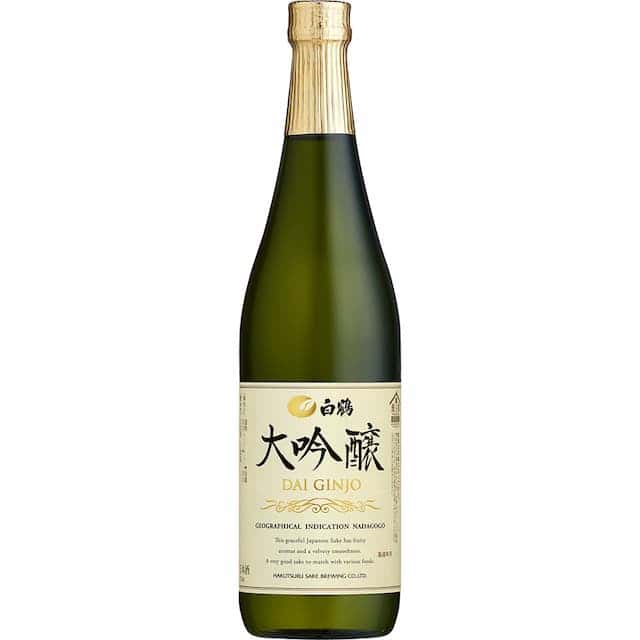

Hakutsuru Daiginjo (白鶴 大吟醸)

It’s a Daiginjo sake with a vibrant aroma and light, refreshing taste. It pairs well with any dish.

| Volume/Container | 720ml/bottle |

| Price | 1,268円 (including tax) |

| Category | Daiginjo |

| Ingredients | Rice, Rice Koji, Brewing alcohol |

| Rice Polishing Ratio | 50% |

| Alcohol Content | Over 15% to less than 16% |

Hakutsuru Shizuka Daiginjo (白鶴 雫花 大吟醸)

Let’s enjoy sake casually! This Daiginjo boasts a moderate alcohol content and a vibrant aroma reminiscent of apples and pears. With its refreshing and gentle sweetness, it leaves a pleasant lingering finish. Named “Shizuku + Hana” (Droplet + Flower), it embodies a fragrant sake (Daiginjo) that blooms like a flower on the dining table with each clear drop. Designed with a botanical atmosphere that complements the elegant and refreshing taste of sake, along with its dignified emotional appeal, it’s a new and casual Daiginjo that fits perfectly into modern lifestyles.

| Volume/Container | 500ml/bottle |

| Price | ¥823 (including tax) |

| Category | Daiginjo |

| Ingredients | Rice, Rice Koji, Brewing alcohol |

| Rice Polishing Ratio | 50% |

| Alcohol Content | Over 9% to less than 10% |

Kikuhime (菊姫 大吟醸)

Through long-term aging, this Japanese sake develops a sweet and aromatic fragrance, along with a mellow flavor and smooth texture.

Crafted using the highest grade Yamada Nishiki rice, this Daiginjo sake boasts a delightful sweet and rich aroma reminiscent of caramel and brown sugar, achieved through the aging process.

Daiginjo FAQ

- How can one identify high-quality Daiginjo sake?

-

High-quality Daiginjo sake can be identified by its clarity, delicate aroma, and smooth taste. Look for sake with a clean, transparent appearance and a fragrance that is floral, fruity, or sometimes even slightly herbal. Additionally, Daiginjo sake often has a refined sweetness balanced with a subtle acidity, creating a well-rounded flavor profile.

- Can you suggest some food pairings that complement the taste of Daiginjo sake?

-

Certainly! Daiginjo sake pairs exceptionally well with light and delicate dishes such as sashimi, sushi, or grilled seafood, as its refined flavors and gentle sweetness enhance the dining experience without overpowering the palate.

Manufacturing method of Daiginjo

Polish the surface of sake rice to achieve a predetermined polishing ratio.

Wash the rice and remove the bran.

Soak the rice in water.

Steam the rice instead of boiling to alter the starch quality in sake production.

After steaming, cool down the rice. At this stage, separate the rice for koji making, yeast starter, and fermentation, adjusting each to the appropriate temperature.

Cultivate koji mold on the main rice used for sake production. This process establishes the mold responsible for creating alcohol.

Create a substance similar to the “mother liquor” of alcohol.

Ferment by adding koji, yeast starter, steamed rice, and water. The liquid during fermentation, called “moromi,” is a preliminary stage of sake. At this stage, add brewer’s alcohol to sake labeled as “Daiginjo,” “Ginjo,” or “Honjozo.”

Press the moromi, separating the liquid (sake) from the solid part (sake lees).

Filter the sake to remove small rice lees and impurities.

Heat the sake for sterilization purposes.

Store the sake for aging, allowing it to develop its unique flavor.

Blend the sake with other sake or dilute it with water to create a more drinkable product. This process also alters the taste, bringing out the unique characteristics of each sake.

出典:riveret

Where to enjoy delicious Daiginjo?

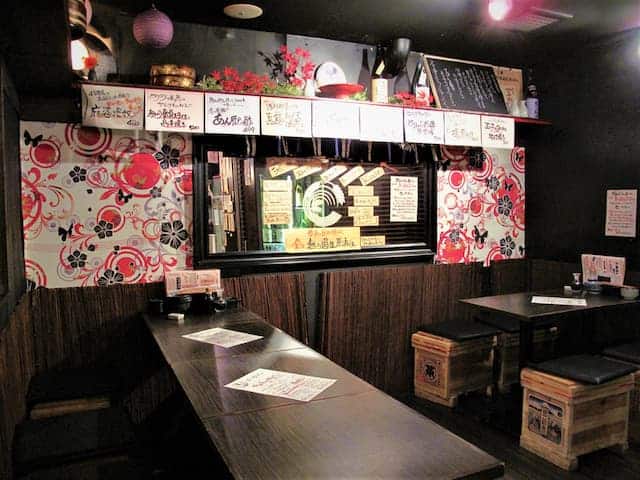

Mangetsu Sakaba (満月酒場 別館BY)

An izakaya called “Mangetsu Sakaba” offers Japanese sake from all over Japan and serves traditional Japanese dishes.

It’s rare to find an izakaya in Tokyo with more than 20 types of “unfiltered fresh sake” at all times. Some of these sakes are hard to find elsewhere, so make sure to check them out. “Unfiltered fresh sake” is sake that’s bottled directly without any filtering, heating, or diluting. Many people love its fresh and bold taste.

These special sakes, known for being challenging to handle, are priced at 890 yen for a glass (150ml) and 560 yen for a shot (90ml).

You can enjoy various kinds of Japanese sake at this place, including “Sugi Isamu Special Junmai” from Yamagata, “Kuroushi Junmai Daiginjo” from Wakayama, “Sawahime Nakatori” from Tochigi, “Tsuki no I” from Ibaraki, “Yawata River” from Hiroshima, “Ju Asahi” from Shimane, “Matsu no Hana” from Shiga, and “Fujibei” from Shiga.

Kanae (鼎)

Established in 1972, “Kanae” is a famous Japanese pub in Shinjuku Sanchome, operating for over 50 years. It’s known for its handpicked Japanese sake and tasty seafood. They offer 50-60 types of sake, loved by sake enthusiasts.

They have special junmai sakes like Aomori’s “Tajima Tokubetsu Junmai” and Kochi’s “Sennakajyak Tokubetsu Junmai.” Also, they have top junmai daiginjos like Yamagata’s “Kudoki Jouzu.” Their “sashimi assortment” showcases their culinary skills. Their fresh seafood, sourced carefully, is served at its best. The “ara daikon,” soaked in rich fish broth, pairs well with sake.

Their interior, made from old house materials, gives a nostalgic vibe. With handwritten menus and a ticking clock, it feels like going back in time. It’s a perfect spot for enjoying good food and sake in a calm atmosphere.

Warayakiya Shinjuku (わらやき屋 新宿)

“Warayakiya Shinjuku” in the heart of Shinjuku offers traditional Tosa cuisine in a stylish Japanese setting. They’re famous for straw-grilled dishes, like katsuo and jidori chicken, cooked at 900°C for intense flavor. They have a variety of straw-grilled dishes, and their sake selection is impressive too. Their sake pairs well with the grilled dishes. The restaurant’s interior is elegant, with different seating options available. It’s conveniently located near Shinjuku’s famous shopping area, making it a great choice after shopping.

For online shopping

For those who want to order or buy Daiginjo in Japan, you can mail it to your home online on Rakuten. You can check out some shops that sell it via Rakuten by clicking below.

And for those who want to order or buy but live away from Japan. You can ship them from Rakuten by following the steps below. Rakuten offers International Shipping Service, so do not worry about how to receive your items. Rakuten Global Express is an online shopping service that allows users to shop at stores in Japan.

Sign up

First, you need a Rakuten ID. If you are already a Rakuten member, you can start using Rakuten Global Express. If you have not registered yet, click here.

Get your personal RGX address

After signing up, you will get a Japanese address: a Rakuten Global Express address.

Shop at stores in Japan

Now that you get yourself a personal RGX address (Rakuten Global Express address). You can shop online in Japan, click here to shop for Daiginjo (not only Rakuten but other online stores are also included).

When you have decided on your items, set the delivery address to your Rakuten Global Express address.

Confirm items

After items are shipped to the RGX address, they will be packed into one package. You also receive an email upon confirming these items and payment.

Once the payment is confirmed, your package will be delivered within a designated period depending on your shipping choice.

Takeaway

Daiginjo is a special kind of Japanese sake, famous for its delicate taste and smell. It’s made using polished rice and careful brewing methods, creating a smooth and flavorful drink. People who love sake appreciate Daiginjo for its high quality and refined taste. It’s known for its smooth texture, mild sweetness, and elegant finish, making it a favorite among sake fans. Whether you drink it alone or with food, Daiginjo is considered one of the best kinds of sake, loved for its exceptional flavor and quality. You can discover your favorite spot to savor Daiginjo with our recommended selections above!

If you are a fan of Japanese alcohol, see below for details or click here!

Comments