Dashi plays an indispensable role in Japanese cuisine, serving as the foundation for countless dishes from simmered foods (nimono) to soups, ohitashi (blanched vegetables), and flavored rice (takikomi gohan). While many people might find the process of making it time-consuming and challenging, this article will demystify its characteristics, share convenient preparation methods for busy cooks. Whether you’re a beginner or an experienced cook, understanding dashi is key to mastering Japanese cuisine.

What is Dashi?

At its core, dashi is a crystal-clear stock that captures the essence of umami – the fifth taste that makes Japanese cuisine so distinctive. Unlike heavy Western stocks that simmer for hours with many ingredients, dashi is elegant in its simplicity, typically made from just one or two ingredients steeped in hot water.

The most common combination is kombu (dried kelp) and katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes), though vegetarian versions using only kombu or dried shiitake mushrooms are also popular. What makes dashi truly remarkable is how it enhances other ingredients without overpowering them, acting as a flavor amplifier that brings out the best in every dish it touches.

Understanding Umami flavor

Umami – the key to Japanese dashi

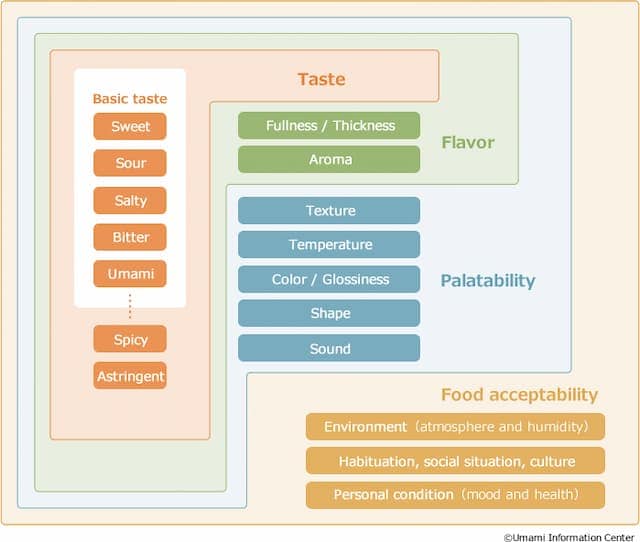

Umami is widely considered the fifth basic taste, along with sweet, sour, bitter, and salty. This savory, meaty flavor is a crucial component of Japanese cuisine, and dashi is the primary vehicle for delivering umami.

The two main umami-rich compounds found in dashi are inosinic acid, which is abundant in katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes), and glutamic acid, which is abundant in kombu (seaweed). When these ingredients are combined to make dashi, the synergistic effect of these umami compounds results in a deeply satisfying, well-rounded flavor.

Mastering the art of dashi-making allows Japanese chefs to harness the power of umami and incorporate it seamlessly into a wide variety of dishes. Whether it’s the delicate, elegant umami of ichiban dashi or the robust, concentrated umami of niban dashi, understanding the role of these essential building blocks is crucial to creating truly exceptional Japanese cuisine.

How people experience the food they eat

The history of umami

Throughout history, human beings have created various seasonings and condiments to improve the palatability of food. Salt has been a familiar flavor-enhancer for thousands of years. Foods such as sugar and vinegar have also been known since ancient times. This is why we can all readily imagine sweet, sour and salty tastes.

Umami too is contained in a variety of foodstuffs, and is familiar to us from the taste of traditional foods such as soy sauce, miso and cheese. However, it is only around a century ago that umami was discovered as a basic taste, and monosodium glutamate invented and launched as an umami seasoning.

The discovery of umami as the fifth basic taste was made by Professor Kikunae Ikeda of Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo). Professor Ikeda noticed the presence of a taste in kombu dashi that did not fit into any of the existing four categories – sweet, sour, salty and bitter. He identified the main taste component to be glutamate, and dubbed it “umami.” Other Japanese scientists later discovered the umami substances inosinate and guanylate.

Ichiban Dashi and Niban Dashi

Ichiban Dashi (一番だし): The Premium First Stock

This ichiban dashi represents the pinnacle of Japanese dashi making, capturing the very first extraction of flavors from the premium dashi ingredients. Skilled chefs meticulously prepare this refined stock by gently adding katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes) to hot, but not boiling water and allowing it to steep for about 10 minutes without stirring. This delicate process preserves the delicate and nuanced characteristics of the stock.

The appearance of Ichiban dashi is particularly striking – it has a beautiful amber or golden color and a crystal clear transparency. However, maintaining this clarity requires careful handling, as vigorous stirring or aggressive squeezing of the katsuobushi can cloud the otherwise pristine broth.

In terms of aroma, Ichiban dashi has an intense, refined fragrance. This is due to the preservation of volatile aromatic compounds, which would normally be lost during intense heating. The flavor profile of Ichiban dashi is equally impressive, exhibiting an elegant, subtle flavor with a clean umami character. When made with a combination of kombu and katsuobushi, the flavors achieve a perfect balance, showcasing the synergistic umami qualities of both ingredients.

Niban Dashi (二番だし): The Second Extraction

While ichiban dashi represents the first and most premium extraction, niban dashi uses the remaining ingredients from this initial process to create a second, equally valuable stock. After ichiban dashi is strained, the remaining katsuobushi and kombu are boiled in water to extract additional flavors.

The appearance of niban dashi is noticeably different from its ichiban counterpart, with a lighter brown hue and a less transparent appearance. This is due to the boiling process, which extracts more compounds from the ingredients and introduces some cloudiness to the broth.

The aroma of niban dashi is also slightly less fragrant than ichiban dashi, as the heating process causes some of the volatile aromatic compounds to dissipate. However, the flavor profile of niban dashi is where it really shines. This second extraction results in a concentrated, robust umami flavor that is stronger and more pronounced than the delicate ichiban dashi. While it may have slight rustic notes, niban dashi’s powerful umami character allows it to hold its own against stronger spices and ingredients.

| Ichiban Dashi (一番だし) | Niban Dashi (二番だし) | |

| Appearance and Color | ・Beautiful amber or golden color ・Crystal clear appearance ・Requires gentle handling to maintain clarity | ・Lighter brown hue than ichiban dashi ・Less transparent appearance |

| Aroma | ・Intense, refined fragrance ・Preservation of volatile compounds due to no-heat extraction | ・Milder fragrance due to heating process ・Can be enhanced with “oigatsuo” (adding fresh katsuobushi near the end) |

| Flavor Profile | ・Elegant, subtle taste ・Clean umami character ・Perfect balance of flavors, especially in combined dashi (using both kombu and katsuobushi) | ・Concentrated, robust umami ・Stronger taste than ichiban dashi ・Slight rustic notes |

Comments